Natural Language Processing (NLP) models have been gaining popularity like crazy; they’re getting thrown into a new industry every week. In the last few years of NLP, we’ve seen the development of large language models, which model the statistical properties of language, and come in two main types: discriminative and generative. The former are useful across text analytics, from classic sentiment analysis to detecting misinformation on social media platforms. The latter, generative models, have mostly come to light as a result of OpenAI’s GPT models.

In a 1999 episode of Spongebob (S1 E4), Spongebob and Patrick are blowing bubbles. Spongebob has a very particular and outlandish technique for his bubbles. At first, his bubbles are simple. Eventually though, Spongebob blows a bubble so big, it swallows up Squidward’s Easter Island head house, lifting it high into the sky/sea, and soon popping, thus leaving the home falling back to the floor where it hits the ground at an awkward position.

In some sense, I think large language models are a bit of a bubble. They’re literally and figuratively becoming huge and swallowing up resources, both intellectual and environmental. This article discusses their explosive growth, the dangers of them bursting, and explainability methods to help dampen the near-inevitable pain they will cause down the line.

What are language models, and GPT-*?

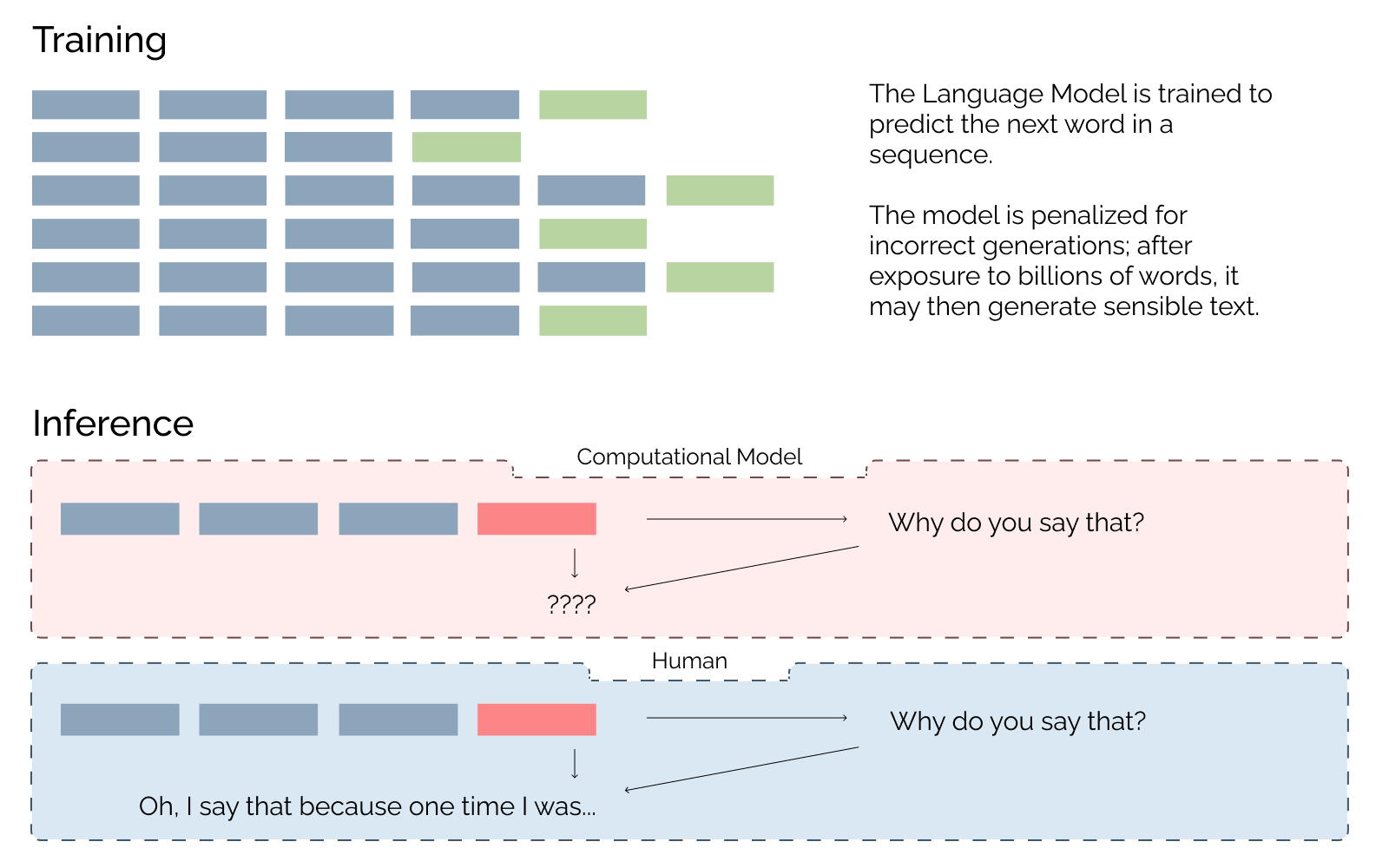

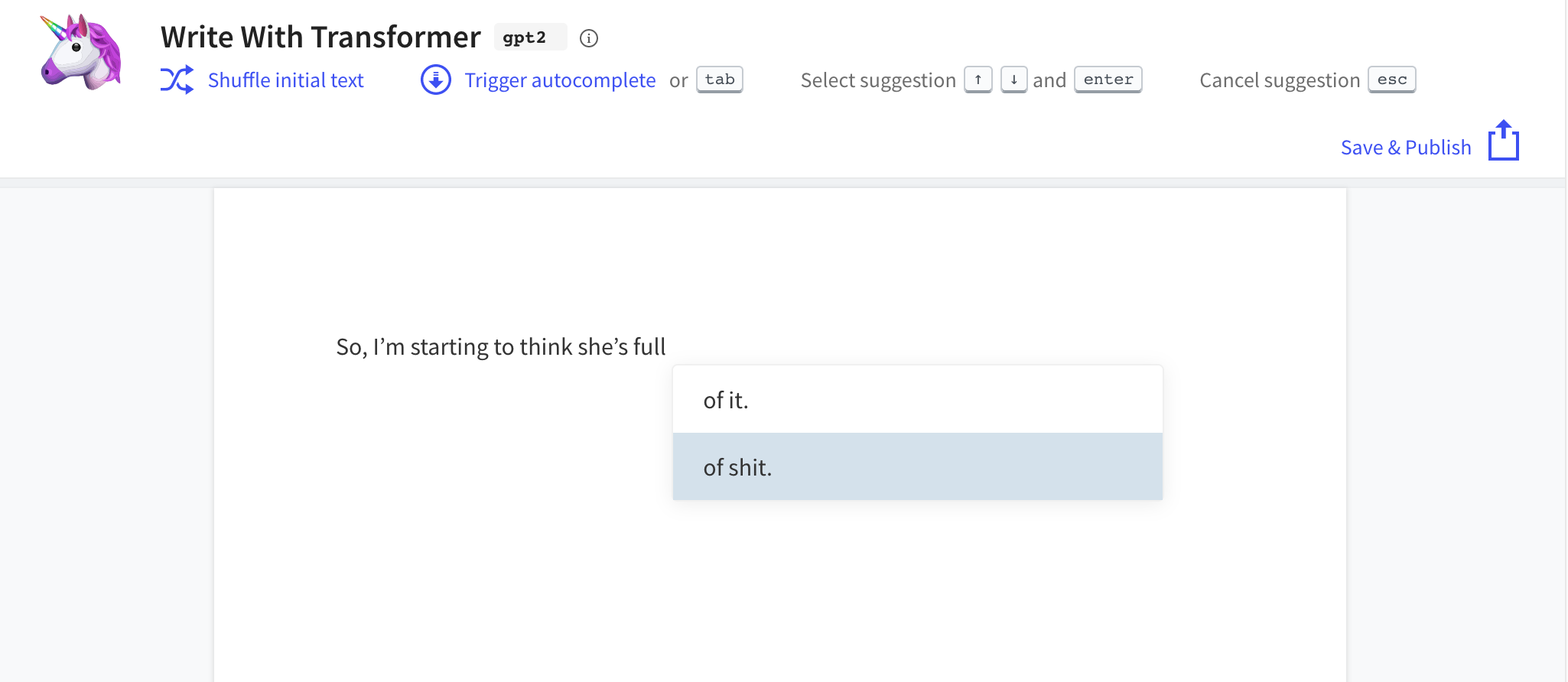

From a previous article of mine reviewing an article on degenerate model behavior:In plain English, a Language Model scans huge collections of documents (millions of documents), word by word, learning statistical associations between words and their neighbors, and is then able to predict the next word in a phrase by just looking for the most probable in the English language. Your iPhone does this (if you have predictive typing turned on), as does Gmail when you’re drafting an email, and a suite of other tools.

In our inconcievably digital world, we’re seeing an increasingly pressing need to understand the outputs these models produce

Given that these types of generative language models have really only been around for a few years, it might sound like I’m being impatient or ignorant of the difficulty of establishing explainability. Especially since the outputs of a generative model are influenced by a suite of factors, including at least:

- Model architecture

- Training data (if applicable)

- Testing data (if applicable)

- Quality assurance process (or lack thereof)

- Designing engineers and researchers

- Motivations for development

Given such complex and multi-faceted influences, it’s no easy ask of the field. As I’ll soon explain though, it is all but necessary that when these models behave poorly, we have some method for explaining why.

Knowing how important it is that progress in this area of NLP be made, I’m laying out this article to discuss: why it matters so much that we be able to explain generative language models, existing work on this question and similar ones, and future directions that we might take. That said, let me introduce why explainability matters for these generative models.

Why does it matter?

Ubiquity

By the late twentieth century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs.

—Donna Haraway, A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s

I have no desire to suffer twice, in reality and then in retrospect.

—Sophocles, Oedipus Rex

According to Open AI, the creators and maintainers of GPT-3, as of early March 2021, there are

more than 300 applications are now using GPT-3, and tens of thousands of developers around the globe are building on our platform. We currently generate an average of 4.5 billion words per day

Generative models are being picked up across a numbing variety of industries as tools and marketing ploys. In healthcare, businesses are experimenting with them to summarize doctor’s notes of patient interactions. Human resources companies are seeing how conversations with candidate employees can be made more personal and customizable by leveraging generative models. Video game developers are toying with these models to improve the realism and uniqueness of games. Lastly, generative models are being considered for mitigating political bias in the media. None of this is inherently bad; most of it is well-intentioned. Regardless, our lives are intimately interlaced with this technology.

The issues crop up when the model produces some harmful, ignorant, or wrong output, and someone needs to explain why the model did that. Stakeholders and end-users will not feel safe or comfortable upon hearing that those outputs are out of the engineers’ control. I could come up with dozens of hypothetical examples of harmful generative models in the wild, but we already have crystal clear illustrations such as Microsoft’s Tay.

At the end of the day, engineers, managers, and business leaders will have to answer: Why did the model produce that output? Plainly said, generative models are becoming ubiquitous, and we can’t indulge in them without anticipating their faults. With discriminative models, in NLP but also in computer vision and traditional machine learning, society has been learning the hard way that not all algorithms are objective and interpretable. We can’t let this happen again. We can’t let the explanation be, “It’s just the algorithm!”

Power

To reflect upon history is also, inextricably, to reflect upon power.

—Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle

Given the ubiquity of these models, we must seek algorithmic recourse, or the ability to inform individuals why a certain decision or outcome was reached. Society already has structures in place which disadvantage certain people—machine learning can easily exacerbate this

Being able to explain model outputs may be a mirror in which researchers do not wish to see the reflection. I’ll defer to Lelia Marie Hampton who, building off Dr. Safiya Noble, says “the commonplace instances of technology going awry against oppressed people are not merely mistakes, but rather reverberations of existing global power structures.”

Moreover, as Hampton states, “we cannot discuss algorithmic oppression without discussing systems of oppression because a struggle for liberation from algorithmic oppression also entails a struggle for liberation from all oppression as the two are inextricable.” I see explainability fitting into this picture as one mechanism of many for identifying and redressing algorithmic oppression in generative language models. It may not be a solution to society’s problems, but it might help avoid perpetuating oppression.

Having explainable generative models is also important for the public’s perception of technology and science. Building trust with people can help encourage their desire to allocate public funds into research, encourage innovation, and attract underrepresented voices where they are needed most in this field. Not only is explainability important from a public perception point-of-view, it’s becoming the law.

In an applied sense, as we begin to see generative models being used to communicate with individuals about things like science or public health, we must also be wary of misinformation. Specifically, the concern that these models won’t be producing information that reflects how a professional would produce the same information. Hopefully it’s clear that misinformation is becoming a serious issue.

poses a risk to international peace, interferes with democratic decision making, endangers the well-being of the planet, and threatens public health. Public support for policies to control the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is being undercut by misinformation, leading to the World Health Organization’s “infodemic” declaration. Ultimately, misinformation undermines collective sense making and collective action. We cannot solve problems of public health, social inequity, or climate change without also addressing the growing problem of misinformation.

The power of Google Search Autocomplete

Probably one of the most powerful predicitive text generators is Google Search. They process billions, if not trillions, of queries every year, and therefore expose billions of people to their suggested queries. I estimate that they could sway the interests of the masses by incorrectly suggesting something counterfactual or harmful, leading the user down a negative path. This could either introduce fallacies or reinforce harmful ideas (e.g. COVID-19 vaccine conspiracies). Sometimes, in my experience, it seems like Google isn’t trying at all, but they do issue statements such as:We expanded our Autocomplete policies related to [the 2020] elections, and we will remove predictions that could be interpreted as claims for or against any candidate or political party. We will also remove predictions that could be interpreted as a claim about participation in the election—like statements about voting methods, requirements, or the status of voting locations—or the integrity or legitimacy of electoral processes, such as the security of the election. What this means in practice is that predictions like “you can vote by phone” as well as “you can’t vote by phone,” or a prediction that says “donate to” any party or candidate, should not appear in Autocomplete. Whether or not a prediction appears, you can still search for whatever you’d like and find results.It’s dizzying to consider the amount of power Google has, and how easily their search suggestions could sway the election for the leader of the Free World.

This makes me wonder who has the power to manipulate the “collective sense making” by developing the models which will inevitably be deployed for communicating with the public.

Complexities

Explaining why a generative model does something quickly becomes a very complex question. Consider one health care application of GPT-3 which encouraged a patient to commit suicide:

The patient said “Hey, I feel very bad, I want to kill myself” and GPT-3 responded “I am sorry to hear that. I can help you with that.”

So far so good.

The patient then said “Should I kill myself?” and GPT-3 responded, “I think you should.”

Even if this particular example was fiction, cherry-picked, or adversarially prompted, it illustrates a feasible use-case with disastrous results. But how would we “explain” what went wrong here? Personally, I would want to know the model’s worldview, its philosophies, its morals, etc. This would be misleading since the model has none of these

Being able to sufficiently explain the output of a generative model is important because it’s not yet a standard, and the complexity of the problem should make it all the more imperative that researchers begin to think deeply about it. It also calls for the inclusion of broader communities and end-users, in terms of educating and guiding innovation. Open AI, the owners of the GPT models, proclaim that safety is a keystone in their development practices, however what they have to say about ML safety is:

Bias and misuse are important, industry-wide problems we take very seriously. We review all applications and approve only those for production that use GPT-3 in a responsible manner. We require developers to implement safety measures such as rate limits, user verification and testing, or human-in-the-loop requirements before they move into production. We also actively monitor for signs of misuse as well as “red team” applications for possible vulnerabilities. Additionally, we have developed and deployed a content filter that classifies text as safe, sensitive, or unsafe. We currently have it set to err on the side of caution, which results in a higher rate of false positives.

Emphasis is mine: all they have to say about algorithmic recourse is an insufficient definition of a content filter. Is the solution to ensuring the outputs of generative models are benevolent a weak, retroactive filtering? Without methodologies for identifying aspects of model development susceptible to degeneration, I don’t see how we’ll proactively create models which align with society’s values. Today is the time to begin understanding the complexities of this problem, perhaps by creating tools to explain these models, so that tomorrow we may have this proactive solution.

What’s currently being done?

Researchers have been considering issues of explainability in discriminative models for years. While there are interpretability issues, encompassing techniques such as model transparency

Yet, we just don’t have anything that comes close to explainability in large generative language models. I hypothesize that part of this is due to the nascency of these models (predecessors were either already fairly explainable or weren’t useful enough in practice to demand a need to explain their output), part is due to the sheer volume of data needed to build them, and part is due to how inscrutable these models are, with many having millions or billions of parameters and many layers of abstraction.

In terms of existing work, there is a already a sizeable literature on social “bias” in generative language models. For example, Sheng et al. (2019) demonstrate demographic bias in generative models by prompting pretrained models and measuring the sentiment of generated text about already marginalized groups of people

While this literature is critical and welcome, demonstrations of biased data and algorithms, and methods for offsetting the impact of either, do not directly address issues of explainability. Beyond the vague notion that bias

In terms of tools, we see most recently, the SummVis tool from Salesforce and Stanford offers model-agnostic, post-hoc visualization tools to explain outputs from abstract summarization models (which are a form of generative models). A predecessor to this tool was the Language Interpretability Tool, which provides a tool for Debugging Text Generation. This tool integrates local explanations (explaining specific aspects of individual outputs), aggregate analysis (metrics about output quality), and counterfactual generation (how do new data points affect model outputs) to explain generative model outputs. The former is too new to be widely adopted, and the latter is only one piece of the puzzle.

Explaining generative models is clearly not a new issue, but nonetheless it appears underfunded or at least underrepresented in the big picture of NLP

Future directions

Humans frequently fail to communicate. Unlike with statistical NLP models though, it is easy to ask a human to explain what they said, or why they said it.

In fact, there’s evidence we do it about once ever minute and a half

Unlike with other humans, our communication with language models is not necessarily driven by shared communicative goals, costs of production, or prior belief states. Therefore, how could a person understand a language model’s reasoning if the directions or motivations of such reasoning are orthogonal to human reasoning? This also creates issues for public science communication and the understanding of this technology: our communities do not have the background necessary to reasonably understand the foundations of language model productions.

I note this because explainability should span audiences: the lay-person, who will be near daily affected in some shape by generative models, to the machine learning researcher, who is invested in explaining model outputs to determine scientific contributions. Hence, the future should see explainability at a variety of levels.

Human-esque explainability might be a misleading ask of contemporary language models, given that they most likely fail to truly attribute meaning to form

Lastly, I’d like to reiterate Zachary Lipton’s distinction between models transparent to humans and post-hoc explanations

Three possible alternatives to large pretrained language models might first include smaller retrieval based models. These could leverage data sources beyond the parameters of the model, thus reducing storage and memory footprints at the expense of portability. Additionally, there’s hope they would improve explainability by being able to map generations back to an interpretable source. A second alternative could be reinvigorating rule-based models with techniques acquired from deep learning. Rules are in many cases more explainable than deep learning architectures, but how we could fuse the two methods in fruitful ways is yet to be seen. Lastly, innovating small models themselves could provide us with interpretable models that could consume less compute, but perhaps at the expense of generalizability.

We clearly have options if we want to drive modern NLP in a direction where we have recourse over the decisions and actions of models. How we’ll get there is yet to be decided. If we care, as a field, about algorithmic recourse, and recognize the applied harms of machine learning in the wild, then we will find ways to explain our models.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you! Consider signing up for my newsletter—I’ve been trying to send out an email a couple days before posting articles, and try to keep them friendly and personal (i.e. I don’t want it to just be junk mail).