I want to do something outside of tech for a second. I want to draw some attention to Edward Hopper and unsolicitedly offer my opinion on his work.

Hopper was an American realist painter, born in 1882 in New York, to a middle-class family. In art school, he shifted his focus from illustration to fine art. He traveled a bit after school, including a trip to Paris in 1906, home of Picasso at the time. Hopper saw some inspiring art, including some Impressionist paintings. This style aptly made an impression on him, and his work thereafter appears almost like a reaction to Impressionism. Hopper got back to the US in 1910 and never left again.

Hopper got some credit for his work during his life, and that’s how he made a living. He traveled around the Northeast and painted scenes he saw in his travels. His wife, Josephine Nivision, ended up posing a lot in his paintings. He painted some landscapes, some urban life, some country life, etc. He died in 1967 after finding a good amount of success in his later career, although there were some new kids on the block which ended up stealing some of the limelight from artists like him (e.g., Jackson Pollack and Mark Rothco).

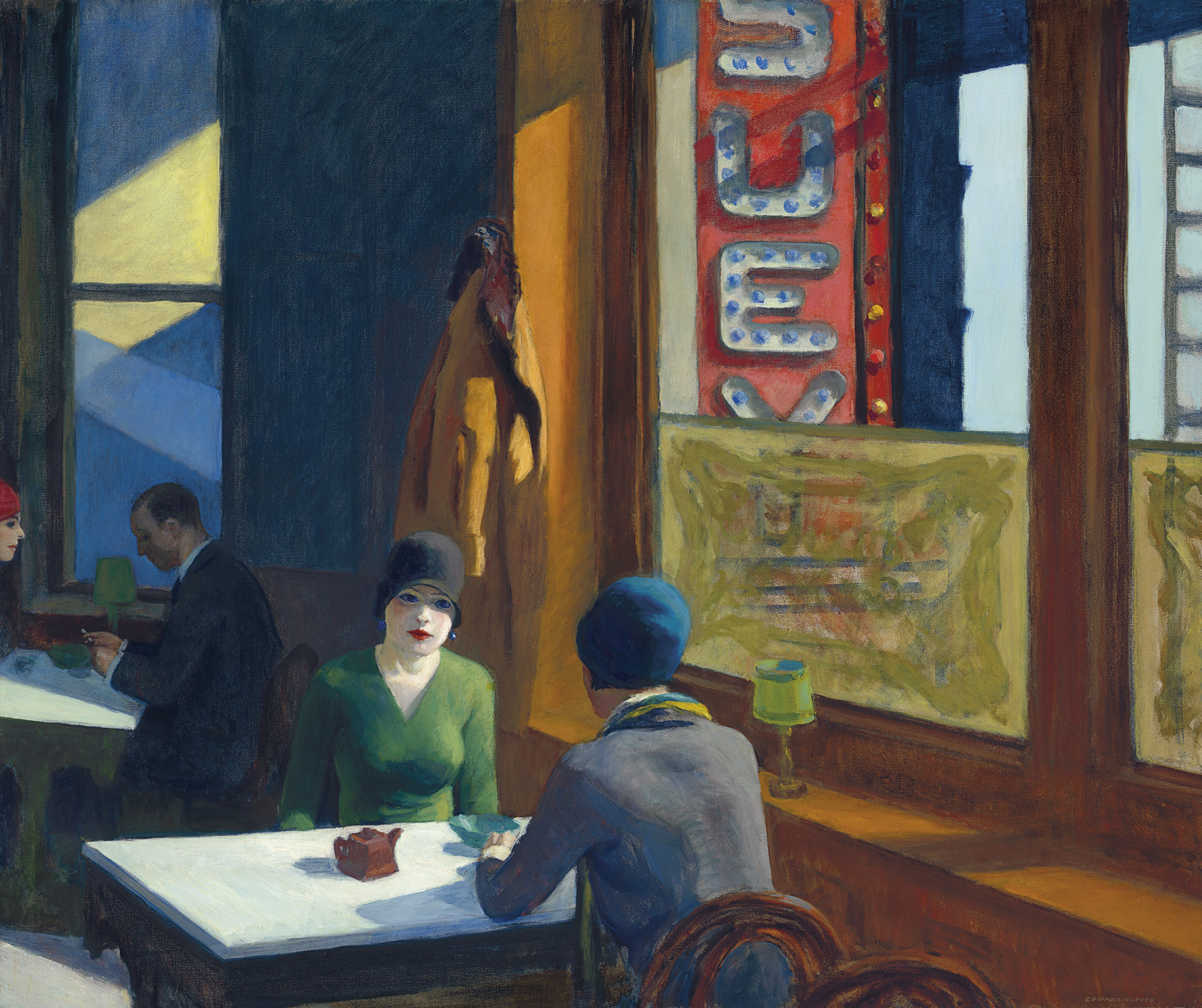

With that necessary biography out of the way, let’s introduce our first piece: Chop Suey.

Chop Suey

Chop Suey was completed in 1929, at a time when America was undergoing significant cultural and soon, economic shifts. Hopper frequented two restaurants believed to have inspired this painting. Something I learned while researching this was that “chop suey” is derived from Cantonese “tsap sui,” meaning “odds and ends”.

We see two individuals sitting opposite of each other at a restaurant, with tea in front of them, in what looks like maybe late morning or early afternoon. There is a couple seated behind them, and outside the window beside them there is a large Googie-style sign reading what we can imagine to say “Chop Suey.” The colors are saturated and vibrant (oranges, greens, blues, reds, yellows). Hopper is clearly interested in expressing something through the intense effect of the lighting from outside. The facial expression on the one focal woman we see is surprisingly dull and pensive. There doesn’t seem to be much activity, conversation, or even emotion between the two patrons.

My first question is, who are these two individuals having lunch together? What do they know of each other and what exactly is their relationship? It’s slightly ambiguous if the person whose back we see is a boyfriend, or maybe a female friend, or perhaps a relative. The relationship between their somewhat solemn lunch and the glitzy sign outside the window is contentious. What’s more interesting: the mystery of their relationship or the fact that this interaction is happening in such a restaurant?

I would imagine that Hopper is making a statement about the changing times, immigration to cities of Asian Americans, the normality of having an uncomfortable lunch with someone at a Chop Suey place. I feel like he might be hoping to create some uncomfortableness in the viewer as well, forcing us to guess about these people and their purpose. I think this theme comes up a lot in Hopper’s work, as we’ll see soon.

Edwardhopper.net interestingly points out: “The high angle of view and the cropping of both the ‘Chop Suey’ sign, seem through the window, and the female customer on the left, all add a sense of strangeness and alienation to the scene.” In 2018, this piece was sold to a private collector for $91.9 million, making it one of the most valuable pre-war American paintings.

Eleven A.M.

This here is his 1926 Eleven A.M. We can clearly see a (almost) naked woman, sitting in a plush blue chair, staring out the window of her apartment. The viewer is seated across the room, staring at the woman from behind a small coffee table with some papers on it. There is art on the wall behind the woman, but it’s meaningless. Likewise, the scene out the window is ambiguous, although we sense that the apartment is number of stories off the ground. The dresser is a pathetic taupe color, the curtains, which appear to lead to red carpeted room, are a dingy blue-green, and the bedding or coat behind the woman are a light off-pink. All these strange colors seem so out of place in this apartment, and to top it all off, the carpet in this room is a green-turquoise! Only in the 1920’s would someone install turquoise carpet. Perhaps the strangest feature of this piece is that the woman, naked, alone, is wearing her shoes. Why would such a being in this situation be wearing shoes?

Obviously, this woman is pensive, perhaps distraught. Her clasped hands, her unwillingness to be dressed (or, why else would she not have clothes?), her lack of a face make this scene incredibly ominous. Why would Hopper place this pitiful woman in such a peculiar room, and give her so little privacy? (A half-pulled curtain for a door, a wide open window.) Is she contemplating a lover? A job? Family? Her own existence, or lack thereof? I suspect she’s looking across a plaza maybe, people watching. Introspecting on her own position in the universe. She might be thinking of grandiose things, considering being dressed in front of an open window seems low on her list of priorities.

Ultimately, we’re drawn into this room as the viewer, and drawn into this woman whose identity and sense of self seem completely abolished. Perhaps it is Josephine: how would that change the piece?

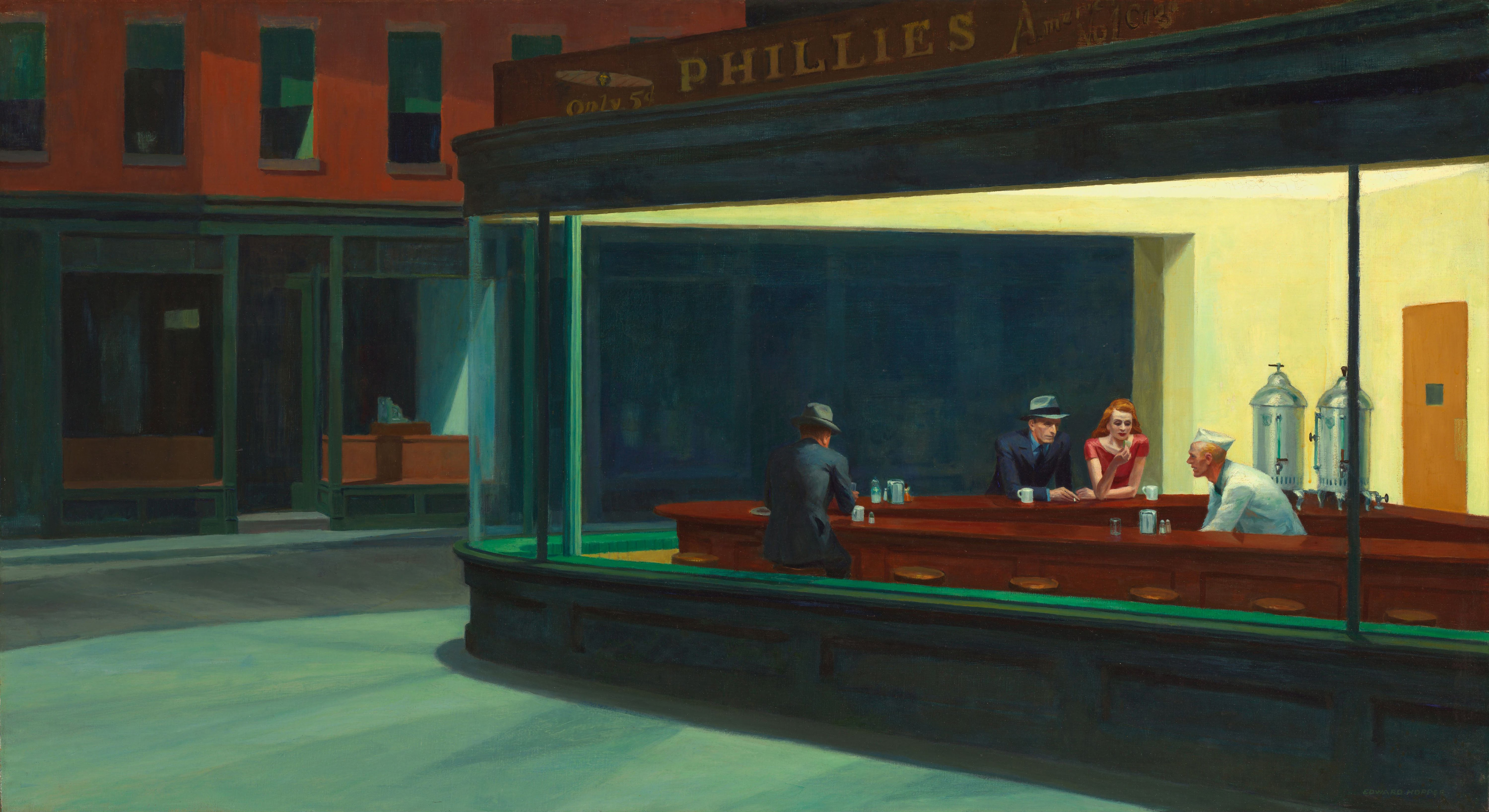

Finally, it’d be hard to write a quick Edward Hopper blurb without talking about Nighthawks.

Nighthawks

Some artists create so many great works that one does not standout when one recalls their work. Picasso, Monet, J.S. Bach, et al. Other artists are certainly prolific, but it’s one piece which they become synonymous, almost metonymous, with. It seems unlike an exaggeration to say that Nighthawks is Hopper’s magnum opus. For good reason, it has captured the creative imaginations of students, critics, and us lay folk for generations.

Despite the unfamiliarity of the scene (I have never been in any of these patrons’ shoes, have you?), it seems familiar. That feeling of being a night owl, out for some reason those around you are not aware of, most likely overcome with thought. What is the man whose back we see thinking of? What about the night hawk himself? (The painting is believed to have been originally titled “Night Hawks,” in reference to the man’s sharp nose, or beak.) The woman is clearly preoccupied with something in her hands, absentmindedly keeping to herself, deep in her own thoughts. The worker behind the counter may or may not be looking at one of the patrons; suppose he’s not, what could he be ruminating about at such an hour? This tension of internal monologue is unbearable. Why is no one smiling? Or talking? It’s frustrating to see these encumbered souls sit around at the bar just withering in their own filth (mental filth, perhaps).

With Nighthawks, one cannot go without commenting, again, on the figure’s loneliness. Half of the persons here are alone, and the other half are arguably also alone (they may be together but they certainly don’t look together in the moment). The one who bothers me the most is the man who’s back we see. Why is he so alone? It’s late at night, or very early in the morning, he’s got nothing, no newspaper, no book, no friend. He couldn’t even be people-watching out the window; the streets are empty. That brings up another point, why is the city so lonely? And in fact, Hopper himself acknowledged that “unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.” What sort of talent does it take for that feeling to be universally captured in an artwork?

Edward Hopper was a visionary of our fleeting existence and perpetual loneliness. He captured and distilled complex emotions and phenomena like mystery, void, helplessness, and despair unlike most others. He froze the vibe (as some say these days) of the early 20th century in his work and has given us a glimpse into what ordinary people were like in the most human situations.

His imagination has given so many after him a desire to depict more than just a scene, and instead a feeling. He tactfully plays with lighting in almost all his work, his colors push reality to the limits, and his people are uncannily familiar despite most of us not having been in their shoes. He’s an artist to soak up and learn from, and his paintings are like teachers.