Overview

Despite our recent global shift toward digital communication, there are still reasons we might come across scanned documents in our every day life. Scanned documents don’t inherently come with searchable or copy-able text embedded within. More often, they’re basically just images. It can be useful to extract the text from these documents though, whether for record keeping or simply organization. Manually transcribing documents is tedious, especially if there are more than about a handful.

This is where Optical Character Recognition (OCR) is useful. We can start with a document, then process that document to not only extract the text on the page, but overlay the text on the document for readability and convenience later on. Most documents we face this kind of problem with are PDFs, a near ubiquitous format by now, hence our focus on tackling OCR with PDFs.

In this short article, I’ll run us through an introduction to OCR for PDF documents in Python, with a focus on using Open Source Software (OSS).

What’s a PDF?

First, a Portable Document Format (PDF) is a file which presents information, including text, images, forms, interactive content, and more. PDFs contain 7-bit ASCII characters, so opening one in a text editor will show you mostly a garble of characters you’ve never seen before. This is all in the Carousel Object Structure, which is almost like a predecessor to XML and JSON. However, what comes off like a mess is actually a detailed layout of the document, including layers with all the text within the document, complex data structures, and embedded images.

Introduction to Tesseract

OCR has a history dating back to the early 1900s, whose progress has picked up pace during the 60s and 70s and has made an occasional jump forward in the last couple decades. Because it is a well known problem, many initiatives have made progress in accuracy, and one in particular is widely acclaimed. This is Tesseract OCR.

Tesseract is an open source OCR engine with more than 100 recognized languages, and a number of useful output types (another image, text, PDF, etc). It is moderately configurable, but has a large following and maintainer community. Most importantly though, in general it works well.

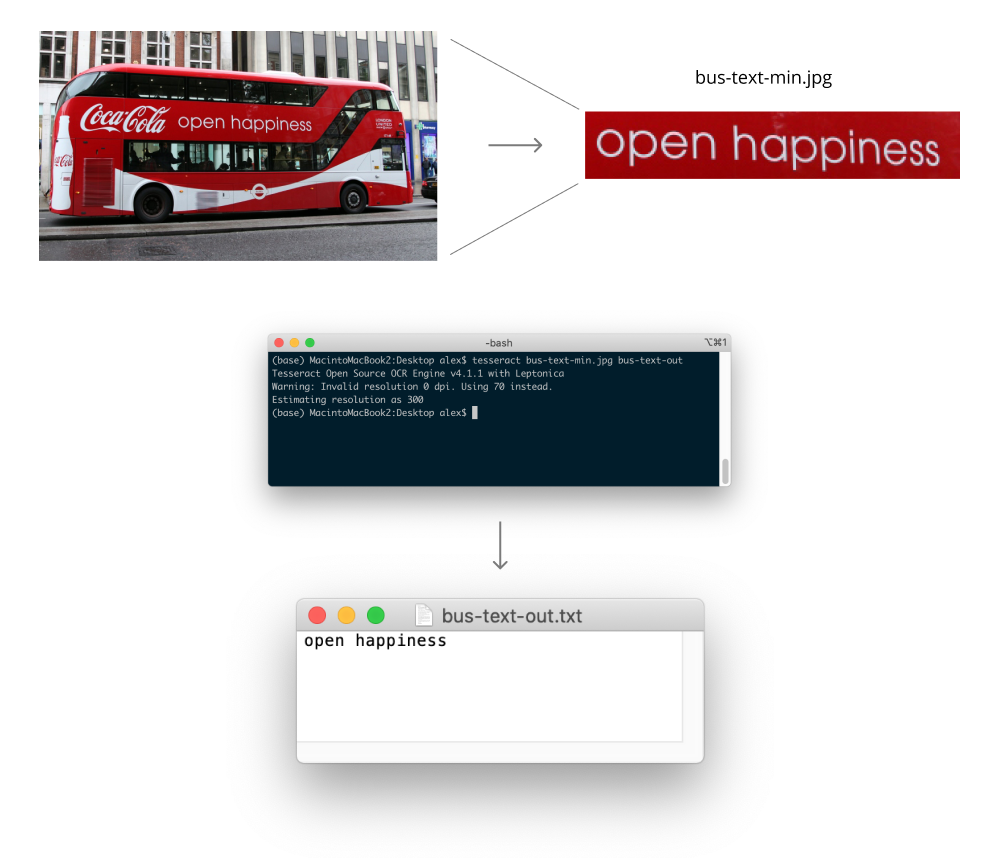

While there are APIs that layer on top of Tesseract, the engine itself is largely written in C++ and used through a command line interface. The engine accepts as input an image, and if it recognizes text within the image, it will attempt to classify the letters and words in the image and then output the transcription.

For example, in the above figure, we see how after cropping an image of a bus to retain mostly just the text, we can run Tesseract which outputs the text in the image.

This is the essence of Tesseract. Its simplicity, efficiency, and accuracy make it an ideal solution for targeted (i.e. minimal content surrounding the text) and fairly readable (i.e. success not guaranteed on Captchas) images.

Introduction to OCRmyPDF

Tesseract works great for images, but as discussed above, most documents come as PDFs, and PDFs are a sophisticated data structure. Tesseract does allow the output of PDFs, but one cannot input a PDF to Tesseract. While we could hack our way around PDFs to apply Tesseract on them, there exists an open source solution which I’ve recently worked with and found useful.

Namely, OCRmyPDF is a specialized command line tool and Python package which is built on a Tesseract OCR engine. OCRmyPDF does accept PDFs as input, and can not only output the text as a companion (sidecar) text file, but also overlays the text directly on top of the underlying images in the PDF. OCRmyPDF essentially pulls out the bitmap images from the PDF, performs a series of pre-processing steps (e.g. denoising, deskewing, etc.), then performs OCR on those images.

Suppose we have a PDF which looks like the following:

Yes, I chose the 2018 tax returns of ProPublica. They’re always investigating people, I think it’s only fair we investigate them too. Besides saving only the most interesting pages in the full 65 page IRS report, I didn’t alter the document at all. You’ll notice you can’t select any of the text in the document though!

OCRmyPDF to the rescue. If we save this document, and in the working folder run the following Bash command:

ocrmypdf propublica-tax.pdf propublica-tax-out.pdf --sidecar propublica-tax.txt

the package will process the original PDF (the first argument), then output the OCR’d PDF to the output file (second argument), and will also output a text file with the extracted text (file provided by the --sidecar flag). Here is the OCR’d file:

While I encourage you to highlight and select text within the document, for those of you on mobile, here is a sample of what’s in the text file:

A For the 2019 calendar year, or tax year beginning 01-01-2018 , and ending 12-31-2018

B Check if applicable

OO Address change

O Name change

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax

Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations)

® Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public

» Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information.

OMB No 1545-0047

2018

Open to Public

Inspection

C Name of organization

PRO PUBLICA INC

D Employer identification number

14-2007220

Clearly, it has flaws. Namely, it’s fairly poor at disambiguating table and cell structures, and special characters are difficult to interpret. It gets some structure correct, but there’s only so much formatting we can represent with plain text files. Overall though, we could do a lot of processing with this text data. Across many tax returns, I’m sure we’d notice plenty of patterns and extracting the most useful information would not be that difficult.

Concurrent Processing of PDFs

OCRmyPDF may work very well in this way should you have only a handful of PDFs to process. If you have dozens, hundreds, or millions of PDFs, this process would take too long. One way to make this more efficient is to use multiprocessing, or concurrency.

We can do this with a little Python, although I’ve recently looked into learning some Go since I hear that concurrency is natively supported with their syntax and functions very well (see this cool concurrency visualization using Go).

Using the multiprocessing native library in Python, roughly, we can spin up multiple processes (spread across however many CPUs you have) that each control an OCR job in parallel. If you have \(N\) processes, and they’ll all able to run in parallel, the time to run the total task will be divided by \(N\). If you have 100 PDFs, and each takes 20 seconds to OCR, this would take 30 minutes in serial—-in parallel on 4 processes, this would take (surprise), 8.3 minutes.

To make a small script to OCR many local documents, it would: first, load the names of the files to process. Second, distribute those files to parallel jobs. Third, execute each job. All of this can be executed in essentially less than 10 lines of code:

import os

from multiprocessing import Pool

import ocrmypdf

PROCESSES = 4

files = [f.name for f in os.scandir('pdfs/')]

chunk_size = int(len(files) / PROCESSES)

file_chunks = [files[i:i + chunk_size] for i in range(0, len(files), chunk_size)]

def ocr_files(file_list):

for input_file in file_list:

ocrmypdf.ocr("pdfs/" + input_file, "pdfs/out_" + input_file)

with Pool(processes=PROCESSES) as pool:

pool.map(ocr_files, file_chunks)

To break this down a little:

- We predefine the number of CPU processes to spawn. This number can be static, or reflect the machine being used (i.e.

os.cpu_count()). - Find the documents to process (in the

pdfs/directory). Take this list of files and group it into evenly sized chunks. - Create a small helper function to iterate over the files given to the process. Here is where we call the OCRmyPDF API.

- Create a process pool with \(N\) processes, and map the chunks of files over the helper function.

There are numerous improvements we could make, but this is a start. We’re not catching exceptions, we’re not allowing processes to recover if they face an error and shut down, we’re not logging, we’re not properly creating file paths (i.e. using os.path.join), etc.

However, this would OCR a decent sized batch of PDFs for the lay person. Hopefully this tutorial is useful to those looking to dip their feet into OCR with Python without spending excessive amounts of time or money on cloud compute or proprietary software. My final comment and question for the reader: what is the best way to say, in verb form, that one will “OCR” a document (to Optical Character Recognize sounds awful)?

If you have any questions or would like (me) to clarify anything, please let me know!

Update (2022-02-21): I originally used the multiprocessing library to create processes for parallel tasks. If I were rewriting this article I might instead take advantage of the pqdm package, which is more user friendly and very helpfully includes a progress bar.