My family celebrated my grandma’s 88th birthday a couple weekends ago. She, however, was prepared to give out gifts to everyone else. Knowing what my family enjoys doing, she mail ordered (from a catalogue, yes) a puzzle for us all to solve. It’s called the Grecian Computer puzzle. Unfortunately, I can’t find any reliable background on it. Barnes and Noble claims it was inspired by an astronomical tool found in an old Grecian shipwreck. I think it’s just a puzzle someone came up with. However skeptical I am of its origins, the puzzle is hard, very hard. My sister, dad, and I took turns trying to solve it and none of us made any progress. Not that we’re numerical geniuses, but collectively we were stumped.

To help you picture what we were up against, here is what the puzzle looks like:

Each of the concentric circles rotates, and the goal is to turn these dials until each of the 12 columns add up to 42.

The dials aren’t purely concentric — some of the spaces are “blank”, revealing the number on the dial below.

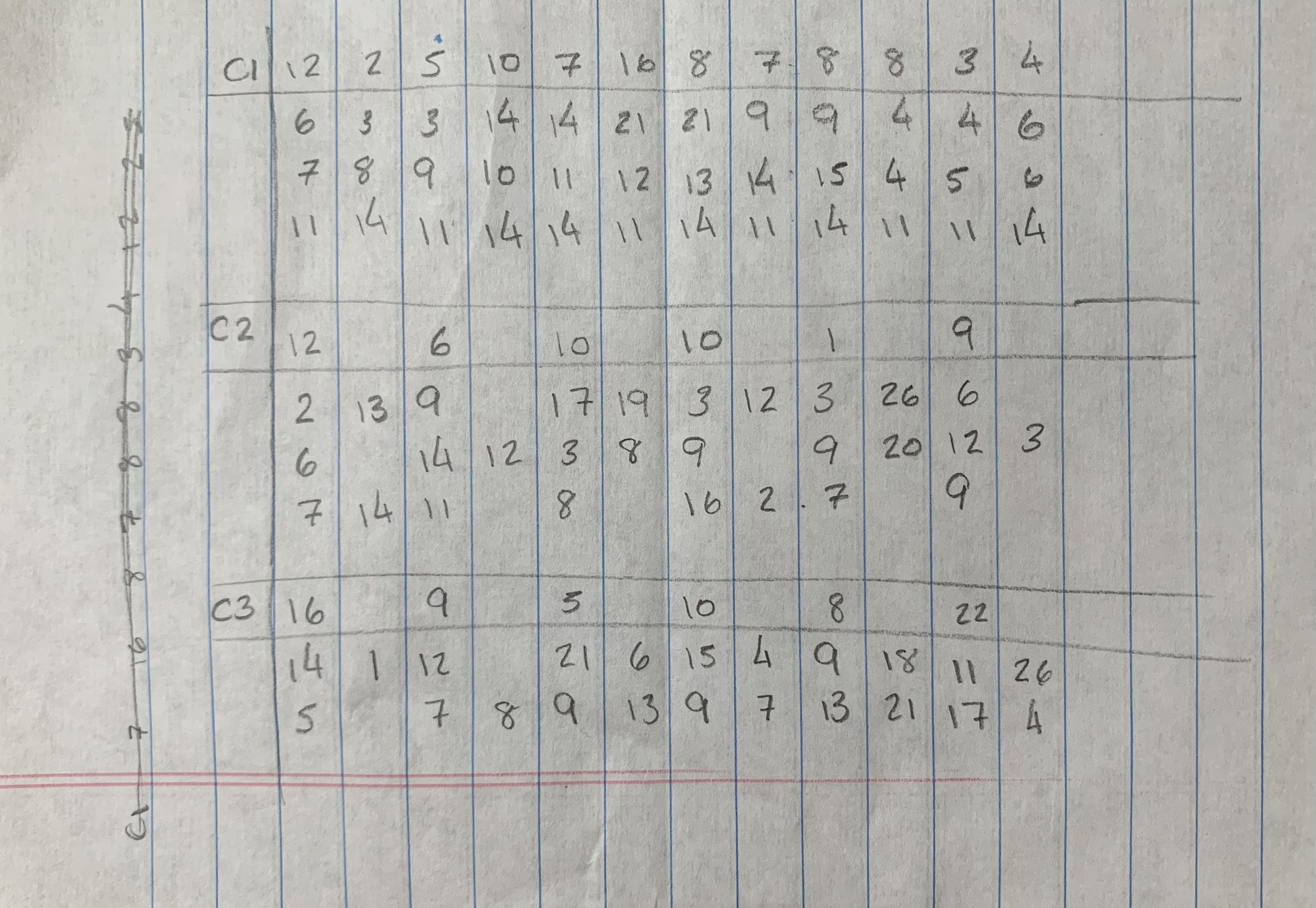

After turning the dials for a while without success, I took out a piece of paper and started writing out numbers. It took me a moment before realizing how to write them out: each dial being a “layer” and represented as a matrix. I could leave a cell empty to represent a hole in a dial. Here’s one of my notes:

This started to make sense in my head and I noticed a couple patterns, but nothing meaningful enough to help solve the puzzle. I thought, Well since these are really just matrices, could we write an algorithm to solve this?

Let me first get it out of the way that yes, I solved the puzzle. Yes, I did it using a computer. No, I have no idea how to solve the puzzle without the computer’s brute force. Puzzles are for meant to be fun, and reveling in Algorithm Land is my version of fun.

That made clear, I’m sure the reader is most interested in the computational solution. Without further delay, I first will describe the solution, then my progress and learnings.

Solution

I represented our puzzle as a 3-dimensional tensor. A tensor is a generalization of a scalar, a vector, or a matrix. A scalar is a 0-dimensional tensor, a vector 1-dimensional, and a matrix 2-dimensional. The puzzle has 5 dials, with 4 rows of numbers, and 12 columns. Naturally then, this is a tensor with shape 5x4x12.

The solution is given to us: all columns must sum to 42. Mathematically, we can represent this solution as a vector of length 12, each value equal to 42.

We have two unanswered questions. First, how do we represent those “blank” or “empty” cells? Second, how do we “rotate” the dials?

My answer to the first is that the “empty” cells in the tensor are set to 0. A zero signals, through masking and multiplication, that the value beneath is used.

My answer to the second is to “rotate” or “roll” a specific axis of the tensor. The matrix gets pushed to the right and the column that falls off gets placed on the left.

I’m intentionally grounding this explanation in metaphors of the physical world. Without the metaphors, we would quickly become lost in terminology.

Another hidden difficulty in this is summing the columns. What’s trivial for the human eye to pick up as a “column” is less so in this computational framework. I thought of this as working down, or outward. First, we consider the innermost or top dial. Suppose on a dial, \(A\), with two numbers (but four spaces) there are

[0, 5, 0, 1]

Then if we sum over each column we get the result: [0, 5, 0, 1].

Suppose there’s a dial underneath, call this \(B\):

[

[1,1,1,1],

[2,2,2,2]

]

How would we add this with the innermost dial? Overlay the first dial onto the second. The first column would be 1 + 2 = 3. Second, 1 + 5 = 6. Third, 1 + 2 = 3. Fourth, 1 + 1 = 2. Resulting in [3, 6, 3, 2].

I represented the innermost dial \(A\) then as

[

[0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 5, 0, 1]

]

To quickly compute the result of \(A\) overlaid on \(B\), solve:

A + (A == 0)*B

where (A == 0) becomes a masking matrix of 1s (True) and 0s (False). Thus this only uses values of \(B\) where \(A\) is empty. Bringing it all together, this sums the values of \(B\) where \(A\) is empty, with all values of \(A\).

We extend this for all five puzzle dials until we have something that looks like:

np.sum(

game[4] +

(game[4] == 0) * game[3] +

(game[4] == 0) * (game[3] == 0) * game[2] +

(game[4] == 0) * (game[3] == 0) * (game[2] == 0) * game[1] +

(game[4] == 0) * (game[3] == 0) * (game[2] == 0) * (game[1] == 0) * game[0],

axis=0

)

Here game is just a copy of the game board after rotating it. Consider game[4] as \(A\) and game[3] as \(B\). Now extend the logic to the next dial, say \(C\), where the values of \(C\) are only relevant where we can see them (i.e. where the values of both \(A\) and \(B\) are 0).

Now what about rotating the dials? Numpy has an np.roll method that performs exactly what we need: rolling an axis of a tensor so that the “columns” are shifted, with the final column being carried over to the front.

Lastly, we must represent the state of the dial somehow. I did this with a vector of length 5, with each element representing the rotation (up to 12) of one of the five dials. The starting point of the game is arbitrary, and doesn’t matter since we can brute force all combinations anyways.

We have a function for summing the puzzle and checking the score:

def equals(layers):

# first roll the board so the dials are at the right positions

sub_copy = roll_board(layers)

# now sum all the columns, for each dial taking into account how it's masked

s = np.sum(

sub_copy[4] +

(sub_copy[4] == 0) * sub_copy[3] +

(sub_copy[4] == 0) * (sub_copy[3] == 0) * sub_copy[2] +

(sub_copy[4] == 0) * (sub_copy[3] == 0) * (sub_copy[2] == 0) * sub_copy[1] +

(sub_copy[4] == 0) * (sub_copy[3] == 0) * (sub_copy[2] == 0) * (sub_copy[1] == 0) * sub_copy[0],

axis=0

)

# do all our columsn equal our solution?

return np.all(s == solution)

We also have a function for rotating the board, according to a given state:

def roll_board(layers):

# first, create a copy of the game (so we don't modify the original)

sub_copy = np.array(game)

# for each of the 5 dials

for i, offset in enumerate(layers):

selected = np.array(game[[i]])

# roll the dial (on axis 2) and keep the new position in the copy

selected = np.roll(selected, offset, 2)[0]

sub_copy[[i]] = selected

return sub_copy

I saw this as a recursive problem, instead of writing out many loops. This recursive function looks like this:

@tail_recursive

def recursive(layers, tally):

# exit condition

if equals(layers):

return (layers, tally)

# create a copy of the puzzle state that may be masked

masked = np.array(layers)

# we want to know if any of the dials have been exhausted

top = np.argwhere(masked == 12)

# if none have, turn the outermost dial one place

if len(top) == 0:

masked[-1] += 1

# recurse with one change in the state

recurse(masked, tally + 1)

# if one of dials has been exhausted, we increment the dial

# just greater than it, and wipe clean the dials less than it

top = top[0][0]

masked[top-1] += 1

masked[top:] = 0

recurse(masked, tally + 1)

We can initiate the algorithm and solve:

recursive(np.array([0, 0, 0, 0, 0]), 0)

(array([0, 5, 9, 2, 7]), 10871)

It took 10,871 dial turns to reach the solution: [0, 5, 9, 2, 7].

Here is what the puzzle looks like at this state, with all columns adding to 42:

Progress and Learnings

I’m glad to be able to share this solution, and I did my best to explain it simply. There was a handful of attempts to get here though, and it wasn’t a straight shot.

First, I didn’t immediately realize that I’d need to mask numbers. I was confused why the columns weren’t adding up digitally like they were on the puzzle. Eventually I understood that numbers on outer dials were being “hidden” by inner dials. I found that I could mask the outer dials by converting the inner dial to “mask” or “no mask”.

I also wasn’t aware of the np.roll method going into this. I thought I was going to have to… roll my own. Luckily, it took me one or two Google searches to find the pre-built roll method. It did however take me some time to understand how best to use it in this case. Through trial-and-error, I rolled different tensors and tried matching the output with what I expected.

It was about this point that a recursive strategy came to mind. I prototyped a looping method, but it seemed too “hardcoded”, messy, and “stateful.” I have not taken any algorithms courses though. My understanding of algorithms, and recursion, is very limited.

I also realized around this time that I wouldn’t be able to continue on without using simplified toy data. The real data was too complex, and if I wanted to prototype with only one or two layers I wouldn’t have a known solution. So, I created a toy dataset of size 3x3x3 (3 dials, with 3 rows, and 3 columns).

I came up with a first recursive attempt, but, surprisingly, it wasn’t recursive enough. I was really only iterating down a single dimension, not all dimensions. So, many of the possible combinations weren’t getting tried out. I paused and thought about what I needed in a recursive function. I tried again.

There were a couple updates to adapt my previous recursive function to the real data. The toy data was necessary for getting the mechanics down, but I needed to see how things would flow in reality. This included putting quite a few print statements in the recursive function.

As I was testing, I hit a RecursionError saying I reached the maximum recursion depth. I had to Google what this meant. I went back to the drawing board to start fresh with some of the implementations I saw online.

I created a new function and again hit a recursion error. This forced me to go learn about (non-)tail recursion and how Python handles this type of computation. I discovered that Guido in fact does not believe that Python should be designed with recursion in mind:

Third, I don’t believe in recursion as the basis of all programming. This is a fundamental belief of certain computer scientists, especially those who love Scheme and like to teach programming by starting with a “cons” cell and recursion. But to me, seeing recursion as the basis of everything else is just a nice theoretical approach to fundamental mathematics (turtles all the way down), not a day-to-day tool.

So trying to use recursion had come back to bite me. I read that Python only allowed at most about 1000 levels deep in a recursive function. After this, the memory stack has too much to keep track of, and opts to fail. Next time I think I will favor an iterative approach, at least when using Python.

I found a snippet of code on a kind person’s blog which catches any tail recursion error, if there is one. If it catches an error, it restarts a new stack of memory after closing out the original function. This allows the recursive function to continue on even if it hits Python’s recursive limit. In my case, this was a good enough solution to carry onward. You can see how this decorator is used in my code above. I copy here the snippet:

class Recurse(Exception):

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

self.args = args

self.kwargs = kwargs

def recurse(*args, **kwargs):

raise Recurse(*args, **kwargs)

def tail_recursive(f):

def decorated(*args, **kwargs):

while True:

try:

return f(*args, **kwargs)

except Recurse as r:

args = r.args

kwargs = r.kwargs

continue

return decorated

Eventually, I hit run and the function carried out for about 5 to 10 seconds. As I mentioned, after 10,871 iterations, the function reached an output. I determined what the board would be at that result and tested it out on the game in my hand. Success!